T hen we speak of art that transcends boundaries, we often think metaphorically—art that crosses cultural divides, challenges social norms, or pushes aesthetic limits. But what happens when an artist literally transcends the ultimate boundary: Earth's atmosphere itself? This is the extraordinary story of Paul van Hoeydonck, whose vision carried human creativity beyond our planet and into the cosmos.

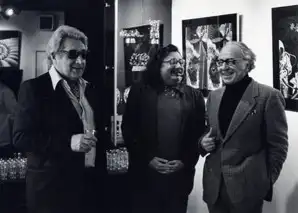

BRUSSELS Van Hoeydoncks short geometric abstract period commences around 1955 with art movements such as ArtAbstrait, Formes and Art Construct. In 1957 he produces his first monochrome collages with slices glued and over painted on the canvas.

The Gravity of Artistic Vision

Van Hoeydonck's early work in the 1950s and 1960s already showed an fascination with geometric forms and spatial relationships that would later find their ultimate expression in the vacuum of space. His sculptures possessed a quality that seemed to defy gravity—not through literal levitation, but through a visual lightness that suggested movement beyond earthbound constraints.

This prescient quality in his work wasn't accidental. Van Hoeydonck was deeply influenced by the space race unfolding around him. As humanity took its first tentative steps beyond Earth, he began to envision art that could accompany these journeys. Where others saw the Moon as a destination for scientific exploration, van Hoeydonck saw it as a gallery waiting for its first exhibition.

"Art is not bound by the same laws that govern our physical existence. While our bodies are anchored to Earth by gravity, our imagination—and the art it creates—can travel anywhere."

— Paul van HoeydonckThe Memorial Impulse

The Fallen Astronaut, van Hoeydonck's lunar sculpture, serves multiple functions that reveal the complexity of his artistic vision. On its surface, it's a memorial—a tribute to the astronauts and cosmonauts who had died in the pursuit of space exploration. But beneath this commemorative function lies something more profound: a statement about human vulnerability in the face of cosmic immensity.

The figure's prone position speaks to our fundamental fragility as biological beings venturing into an environment utterly hostile to life. Yet its presence on the Moon also represents triumph—the triumph of human will, creativity, and the irrepressible urge to leave a mark, to say "we were here" in the most unlikely of places.

The figure's prone position speaks to our fundamental fragility as biological beings venturing into an environment utterly hostile to life. Yet its presence on the Moon also represents triumph—the triumph of human will, creativity, and the irrepressible urge to leave a mark, to say "we were here" in the most unlikely of places.

Time and Permanence

One of the most fascinating aspects of van Hoeydonck's lunar artwork is its relationship with time. On Earth, art is subject to the ravages of weather, pollution, and human interference. Paintings fade, sculptures erode, and even the most carefully preserved artifacts eventually succumb to entropy. But on the Moon, in the absence of atmosphere and weather, the Fallen Astronaut exists in a state of suspended animation.

This permanence—or near-permanence—gives the work a quality that no earthbound art can possess. It becomes not just a sculpture, but a time capsule, a message to future generations that will remain largely unchanged for millennia to come. In this sense, van Hoeydonck has created perhaps the most enduring artwork in human history.

Van Hoeydonck's achievement also raises profound questions about art, ownership, and accessibility. Who owns the Moon? Who has the right to place art there? These questions become even more complex when we consider that the Fallen Astronaut was placed without fanfare, without public announcement, discovered only after the fact by those following the mission closely.

"The Moon doesn't care about our earthly divisions—national, cultural, or artistic. It simply receives what we bring to it and holds it in its silent embrace."

— Paul van HoeydonckLegacy and Future

As we stand on the threshold of a new era of space exploration—with missions to Mars, asteroid mining, and the possibility of permanent human settlements beyond Earth—van Hoeydonck's vision becomes increasingly relevant. He has shown us that human expansion into space need not be purely utilitarian. We can carry our culture, our art, our deepest expressions of what it means to be human, with us to the stars.

The Fallen Astronaut remains alone on the Moon, a silent sentinel watching over the lunar landscape. But it is not truly alone—it carries with it the hopes, dreams, and creative spirit of all humanity. In placing this small figure on the Moon's surface, Paul van Hoeydonck didn't just create a sculpture; he created a bridge between worlds, a testament to the power of art to transcend any boundary, even the vast emptiness of space itself.

As we stand on the threshold of a new era of space exploration—with missions to Mars, asteroid mining, and the possibility of permanent human settlements beyond Earth—van Hoeydonck's vision becomes increasingly relevant. He has shown us that human expansion into space need not be purely utilitarian. We can carry our culture, our art, our deepest expressions of what it means to be human, with us to the stars.